Milletlerarası Adalet Divânı’nda hâkimlik de

yapmış olan Sri Lankalı hukukçu Cristopher Gregory Weeramantry (1926-2017), Islamic Jurisprudence: An International Perspective adlı kitabında dikkate değer tezler ortaya koymaktadır. Bunlardan biri,

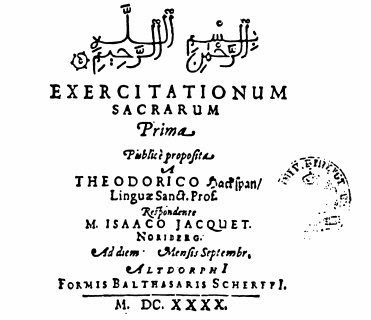

İslam hukukunun Batılı devletlerarası hukukun gelişmesindeki tesirine dair tezdir. Bu tezi, bilhassa devletlerarası hukukun kurucularından kabul edilen Grotius (1583–1645) üzerinden 19 madde ile temellendirmektedir. Yazar, her nekadar maddelerin teker teker ele alınması halinde kesin veya inandırıcı olamayabileceklerini söylese de; maddelerin tamamı dikkate alındığında Grotius'un Müslüman hukukçuların tesirinde kalmış olabileceği tezinin sistematik bir şekilde tahkike değer olduğunu ifade eder.

THE

IMPACT OF ISLAMIC INTERNATIONAL LAW ON WESTERN INTERNATIONAL LAW [1]

The preceding sections set out some of the

many areas in which Islamic international law had worked out a set of mature

juristic principles. This raises the question whether this was a legal

phenomenon separate from and unrelated to the resurgence of international law

that occurred in the West from the seventeenth century onwards. In other words

was this Western development an independent take-off or did it draw upon the

pre-existing body of Islamic knowledge?

(a)

Some General Observations

Any study of Western international law

proceeds upon the tacit assumption that it was the West which triggered off the

development of international law and that international law as we know it was a

Western creation. It is submitted that such a conclusion is untenable for the

following reasons: first, the prior existence of a mature body of international

law worked out by accomplished Islamic jurists in textbooks upon the subject is

an incontrovertible fact.

Secondly, the flow of knowledge in all

departments of science and philosophy from the Islamic to the Western world,

commencing from the eleventh century, is likewise an indisputable fact.

Thirdly, the fundamental rule of Western

international law, pacta sunt servanda, worked out by Grotius in the

seventeenth century is also the fundamental rule of Islamic international law,

where it is based upon Qur'anic injunctions and the Sunna of the Prophet.

Fourthly, there had been contact between

Christian and Islamic civilisations both in war and peace for many centuries

dating back to the Crusades. The crusaders, encountering such monarchs as

Saladin, saw the observance by them of principles of international law, including

truces between the warring parties during which the rival leaders even met at

convivial social gatherings. Peaceful contact through trade likewise exposed

the West to Islamic concepts of international trade, and influenced Western commercial

law. Against this background it seems unrealistic to suggest that the West

remained unaware of the body of international law worked out by the Islamic

jurists.

Fifthly, although there is no doubt that a

great deal of original Western thought went into the elaboration of the current

principles of international law, some at least of the original impetus both in

regard to the general concept and in regard to a number of specific ideas must

clearly have come from the world of Islam - the only power and cultural bloc

comparable to that of the world of Christianity. The philosopher looking for

universals in the realm of international relations could not possibly neglect

this source.

Sixthly, Western scholars were not insular

in their attitudes when they set off the brilliant cultural and intellectual

resurgence which led Europe to world supremacy. They built their humanistic,

literary and legal traditions on whatever foundations they could draw from the

ancient classical civilisations of Greece and Rome. In relation to the vital

discipline of international law there was no literature from Greece and Rome

comparable to their literature in private law. We do not have treatises dealing

with such questions as the binding force and interpretation of treaties, the

duties of combatants, the rights of non-combatants or the disposal of enemy

property. The only body of literature in this discipline was the Islamic.

Seventhly, a knowledge of Arabic was part

of the literary equipment of the accomplished fifteenth- and sixteenth-century

scholar, particularly in Spain and Italy. Arabic literature was hence not a

great unknown in the days when the first seeds were being sown of what was to

become Western international law. This brief survey will be seen in a practical

context when we note that Article 38(1)(b) of the Statute of the International

Court of Justice, requires the International Court of Justice to apply “the

general principles of law recognised by civilised nations”. Having regard to

the large number of Islamic nations now members of the United Nations, the

international law of Islam is a body of knowledge which the world court cannot

afford to ignore. Indeed it must necessarily make an impact upon the content of

contemporary international law.

(b) The

Possible Impact upon Grotius

Since Grotius is often regarded as the

focal point for the commencement of the discipline of international law, the

following observations will be of interest. No one of them is conclusive or

even persuasive by itself but together they may present a thesis deserving of

more systematic scholarly examination.

(i) Grotius' mission, as perceived by

himself, was to study the totality of human history, as far as was available,

and to extract from it a set of practical rules which mankind must necessarily

follow if the nations were to live together. For this purpose he made a

monumental study of world history and could not have failed to consider Islamic

history. Indeed one of his observations was that the Christian nations behaved

in war in a manner which compared very unfavourably with that of pagan nations.

(ii) The Spanish jurists who immediately

preceded Grotius would necessarily have affected the thinking of Grotius, but

to what extent we cannot say. If indeed the Spaniards themselves had been

influenced by Islamic learning on this matter there is here an unresearched

area of possible indirect influence on Grotius by the Islamic jurists.

(iii) Grotius was not entirely unaware of

the existence of some at any rate of the rules of Islamic public international

law. In Chapter X, article 3 he mentions postliminium - the principle of

international law restoring to their former state persons and things taken in

war, when they revert into the power of the nation to which they belonged.

(iv) Grotius was searching for a secular

basis for the world order of the future now that the spiritual authority of the

Church had broken down. He was reaching out towards a new universalism. The

thought and learning of a major world culture which had produced a developed

jurisprudence of its own is scarcely likely to have been ignored.

(v) When one considers that neither the

Greeks nor the Romans had produced a coherent theory of international law and

that the medieval Christian Church was only groping towards this concept, it is

unlikely that Grotius, who was probing universal knowledge and experience to

evolve his system, would have failed to notice the only systematic writings

ever produced thus far upon the topic.

(vi) It is true the language barrier could

have stood in the way of such cross-fertilisation. Yet we must bear in mind

that Grotius was far closer in history than we are to the period when Arabic

learning had diffused through Europe. Arabic scholarship was strong in Spain,

and The Netherlands were historically closely linked in a European system which

had for long accepted The Netherlands as a sphere of Spanish influence and

dominion. Since the time of Grotius the cultures have moved much further apart

and it would be wrong to assess Grotius' access to these materials in the light

of their modern remoteness.

(vii) Grotius finalised his De Jure Belli

ac Pacis in France, where he had fled after his escape from imprisonment in the

fortress of Louvestein. In France he worked on his book in the chateau of Henri

de Meme, where another friend, de Thou, “gave him facilities to borrow books

from the superb library formed by his father” (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1947

edn, vol. 10, p.908). A 'superb library' in France in the early 1600s could not

have been without a stock of Arabic books and other materials on Islamic

civilisation. Moreover, if Grotius had no Arabic himself it is highly unlikely

that he could not have found a translator in France.

(viii) Grotius was also a writer on

Christian apologetics, in which sphere he needed to defend the principles of

Christianity against all rivals. His book, De veritate religionis Christianae,

of 1627 (two years after De Jure Belli ac Pacis), was indeed used as the

standard manual on this subject in Protestant colleges until the eighteenth

century. It was a book, moreover, which was intended for missionary purposes

and one of its target audiences was the Arab world - as is evidenced by its

translation into Arabic in 1660 by Pococke, the Oxford Arabist who taught

Locke. The Arab world was not therefore a world too far removed from Grotius.

(ix) The Arab world was also close to the

Low Countries in another sense. Dutch vessels were beginning to ply in eastern

waters where Arab seamen had hitherto held sway, challenged only by the Portuguese.

They were sailing as far afield as the Islamic islands of the East Indies.

Indeed Grotius was retained by the Dutch East India Company as their advocate.

The case which in fact drew him to a study of international law, for which he

was retained by the Dutch East India Company, concerned a Portuguese galleon

captured by one of the Dutch captains in the Straits of Malacca; the company

sought to keep it as a prize. Grotius needed to demonstrate the untenability of

the Portuguese claim that eastern waters were their private property. In

demolishing this theory of mare clausum and making the high seas free to all

nations, rival theories to mare clausum, especially rival theories pertinent to

the area could not have escaped his attention. The well-developed maritime law

of the Arabs must necessarily have been one of his areas of enquiry.

(x) Nor was contact with Islamic rulers

confined to the East. In the days of sail, when vessels hugged the coast, Dutch

vessels sailing east had necessarily to deal with Arab settlements on the

African coast. Portugal, Holland's rival in eastern waters, had indeed had

diplomatic dealings with them as well as with black African rulers, e.g. the

kings of Benin and Bakongo (Sanders, 1979, p. 57). Grotius, the adviser to the

East India Company, could not afford to be uninformed of the best diplomatic

means of advancing Dutch influence in the interplay of African, Arab,

Portuguese and Dutch interests.

(xi) We know as a matter of history that

diplomatic intercourse between Muslims and Christians had been maintained for

many centuries, going back in fact to the days of the First Exile of the

Prophet's followers, when, under persecution, they sought refuge in the

territory of the Christian king of Ethiopia. This was even before the

foundation of the Islamic state. Later the classical principle of jihad held

sway, i.e. the principle of a permanent state of war between Islamic and

non-Islamic nations (see, on this, the discussion on jihad, pp. 145-9). This

was, however, only an interlude (see Khadduri in Proctor, 1965, p. 33), and the

principle of peaceful relationships among nations of different religions

replaced the classical principle of jihad. Jihad was no longer adequate as the

basis of the relationship between Islamic and other states and Muslim rulers

made treaties establishing peace with non-Muslim states extending beyond the

ten-year period provided under the sacred law. Islamic and Christian states

passed through a long period of coexistence - a period which began as a guerra

fria (cold war) to use the words of the thirteenth century Spaniard, Don Manuel,

and ripened into a relationship conducted on the basis of equality and mutual

interests. In 1535 there occurred a landmark event - the treaty of 1535 between

Suleiman the Magnificent and the King of France laying down the principles of

peace and mutual respect - terms offered also by articles 1 and 15 to other

Christian princes willing to accept them (Khadduri, in Proctor, 1965, p. 34).

This was a clear acceptance of international relationships based on peace and

on the very principle pacta sunt servanda which Grotius was seeking to

universalise. Islamic learning on this very matter, which was one of the basic

teachings of Islam, was close indeed to the heart of Grotius' doctrine. With

his vast erudition could he have failed to perceive it?

(xii) Grotius was considered by the Dutch

authorities of the time to be “a high authority on Indian affairs” (Clark,

1935, p. 60) and had written a masterly survey of Dutch progress in the East

Indies which had appeared in the Annales. He had also written his De Jure

Praedae arising from his interest in the prize matter mentioned above. For his

expertise in these matters he was selected by the States-General to represent

the Dutch East India Company in the negotiations that took place in London in

1613 on the respective trading rights in eastern waters of the British and

Dutch East India companies - a negotiation which the Dutch based largely upon

the rights accruing to them from trading treaties with the Muslim sultans who

ruled in the Malay archipelago, Grotius, as the recognised expert on these

rights, must have dipped into such Islamic international and treaty law as he

could find, e.g. in regard to treaty rights with the Sultan Ternate, about

which there was much discussion at the London negotiations. Indeed it was

Grotius who presented the Dutch case in a long speech at an audience before

King James who at that stage was attempting to handle British foreign affairs personally.

See generally Clarke (1935) on Grotius' mission to London on behalf of the

Dutch East India Company.

Islamic international law became relevant

to such negotiations in another way as well, for the more powerful Islamic

sovereigns such as the Moghul emperors were averse to binding themselves by

treaty to foreigners in respect of trading matters, for treaties involved

compliance under Islamic law and they preferred to preserve their freedom of

action by issuing imperial firmans or grants of trading rights unilaterally.

The significance of such settled diplomatic practice could not have been lost

on Grotius, or indeed on any of the major negotiators or jurists involved in

eastern affairs.

(xiii) It is known that Grotius was in

regular correspondence with Admiral Cornelis Matelief de longe on the policy

that should be pursued by the Dutch in eastern waters (Clark, 1935, p. 61). To

advise the admiral on the course he should pursue, especially in relation to

the Muslim sultans and treaties with them, it would have been necessary for

Grotius to dip into some sources of Islamic legal knowledge.

(xiv) The documents prepared by Grotius for

the London negotiations argued that the treaties with the Muslim sultans about

spices were fully in accord with natural equity and the law of nations (Clarke,

1935, p. 77). He argued that the natural law gave peoples liberty to make their

own treaties and that the “Indians” were bound by the fact of their consent to

give the Dutch a trading monopoly. The fact that honouring of contracts is a

fundamental tenet in Islamic law is not likely to have been overlooked. The

fundamental questions involved in the London discussions were the rights of

extra-European states and of European states in relation to trade and treaties

with them (Clarke, 1935, p. 81). The British reply to the Dutch case of treaty

rights was that such treaties were not legally effective (Rubin, 1968, p. 120).

(xv) It is to be noted that the question of

the validity of treaties and trading arrangements between Christian and

non-Christian nations was the subject of contemporary and even later juristic

debate. Gentili, for example, (1933, p. 31A), was of the view that such

treaties were valid and so was Vattel (1916, p. 122). Robert Ward (1973, p.

332) was critical of these treaties on the basis that they “had the effect of

amending the law of nations”. For a reference to this controversy see Singh,

(1973) pp. 115-16. In arguing for the validity of such arrangements Grotius

would necessarily have consulted the Spanish authorities as well as such

literature he could lay his hands on, regarding the attitude to treaties of the

legal system of the other contracting parties, namely the Islamic law.

Negotiation by European rulers with Islamic

sovereigns had been taking place for some time. For example, we have records of

the letter of Queen Elizabeth to the Emperor Akbar of India – “the most

invincible and mighty prince Lord Echebar (Akbar)” - requesting him to receive

her subjects favourably and grant their request for trading privileges (Singh,

1973, p. 115). A similar letter was addressed by King James to Akbar after

Akbar's death (which was as yet unknown in London) (Dodwell, 1929, p. 77). The

Islamic law background to such negotiations could scarcely be described as irrelevant

to all this activity which was taking place in Grotius' time and in the midst

of which he was one of the chief counsellors.

(xvi) One of Grotius' predecessors, whose

influence Grotius acknowledges, was the Spanish Dominican, de Victoria. The

preface to a recent reprint of de Victoria's work (Nys, 1964) examines the

various Spanish writers on international law who wrote before Victoria and must

necessarily have influenced him. Among them was King Alfonso X of Castile,

whose Las Siete Partidas of 1263 has been described as “A monument of legal

science, curious alike for the number of topics treated, and for what one might

call the precocity of a great number of its provisions which really are far in

advance of the time when they were put forth” (Nys, 1964, Introduction, p. 62).

Nys continues:

The Siete Partidas deals with

ecclesiastical law, politics, legislation, procedure and penal law; the law of

war is the subject of extremely detailed regulations. In the second Partida

some chapters are given to military organization and to war. As regards war,

much is borrowed from the Etymologiae of St. Isidore of Seville ... and in many

respects the influence of Mussulman law is very apparent. Maritime law is also

dealt with.

It is known, for example, that the rules in

the Sieta Partidas that booty should be delivered to the authorities for

distribution and that the treasury keep one-fifth of it were adopted from the

Islamic law (Nussbaum, 1954, p. 52).

(xvii) Reference must be made to St Thomas

Aquinas, himself a Dominican who wrote on the law of war and gave form to the

rather inchoate views held till then in the Christian world in relation to war.

His views on lawful conduct in war have made a lasting impact upon Western

international law and must, of course, have heavily influenced Victoria. We

have pointed out elsewhere that Aquinas was very familiar with the Arabic

writings, especially of Averroes, from whom he drew heavily in composing his

Summa Theologica. The Islamic principles relating to the laws of war were

certainly not a closed book to him in forming his views on just conduct in war

and must have had their impact on Victoria and in turn, even indirectly, on

Grotius. Indeed there is direct reference in Grotius' work to the writings of

Aquinas (e.g. Chapter 7.33 of De Jure Praedae).

(xviii) We must note also that Grotius was

preceded not merely by one Spanish theologian who wrote on the laws of war, but

by many, such as Suarez and Ayala and others going all the way back to King

Alfonso and beyond. All those writers wrote against the background of a

dominant Islamic culture and could not have been unaware of or uninfluenced by

it. For example, Suarez was born in Granada in 1548, barely half a century from

the time when it was the last stronghold of the Moorish kings in Spain. Suarez'

De Legibus appeared in 1612 and there is reason to believe that Grotius read it

with interest and was influenced by its seminal ideas. On the influence of

Suarez on Grotius, see Scott (1939) pp. 17a-21a. “In any event, whatever his

motives might have been”, says Scott, the distinguished former President of the

American Institute of International Law, “the fact remains that the great Dutch

jurist was acquainted with the De Legibus or he would not have cited it. And in

view of this fact and the marked similarity between certain of his own concepts

and those of the Spaniard, it is difficult to believe that in preparing his

treatise On the Law of War and Peace, Grotius failed to avail himself fully

(though without due acknowledgement) of Suarez” masterly treatment of natural

law and the law of nations.' (Scott, 1939, pp. 20a, 21a).

(xix) It must be noted, finally, that

medieval European libraries carried the Arabic treatises on law. Charles S.

Rhyne, President of World Peace Through Law, in his treatise on international

law (1971, p. 23) notes this fact in observing that Islamic Law made

substantial contributions to international law and theory. He notes also that

Western scholars such as Victoria, Ayala and Gentili came from parts of Spain

and Italy where the influence of Islamic law was great; that great jurists and

theologians like Martin Luther studied Arabic; and that Grotius recognised the

humanitarian laws of war of the so-called “barbarians”. It is to be noted also

that Suarez makes free use of a range of prior Spanish writers and that there

are frequent references to King Alfonso's Las Siete Partidas, which as pointed

out earlier, reflected very clearly the influence of Islamic law (for numerous

references to Las Siete Partidas see Scott, 1939).

The question, of course, remains: why in

the extensive writings of these various publicists are the direct references to

Islamic law so scant? There are copious references to the Old and New

Testaments, to Roman and Greek wars and episodes and to the classical writings

of Greece, Rome and Judaism, but scarcely any to the Islamic sources.

It is submitted that the answer is not far

to seek. In the intensely Catholic and Christian atmosphere in the midst of

which those writers - all deeply committed Christians - wrote, Islamic works

could not possibly be cited as authority. It would have been not merely lacking

in authority but counter-productive as being heretical and a source which

Christians ought not to accept. Seeking legitimacy for these views in a

Christian world which was drifting further away from Islamic and Arab culture,

it was not surprising that they distanced themselves both consciously and

unconsciously from these sources.

Although the specific sources came to be

more and more remote, the juristic principles, the classifications and the

range of concepts contained in the Islamic texts were becoming integrated into

the corpus of later writing. It is submitted that there is sufficient intrinsic

evidence of this linkage to make out a case worthy of further investigation.

Referanslar:

[1] C. G. Weeramantry, Islamic Jurisprudence: An International Perspective, MacMillan Press: Hong Kong, 1988, s. 149-158